In The Harlem Hellfighters, a graphic novel by Max Brooks, a World War I regiment comprised of black soldiers gets unexpected respect in Europe for their bravery on the battlefield. In the midst of this, one character flashes back to his pre-war life as a janitor in a movie theater. In 1915, just a few years before the war began, he had watched a huge white audience embrace a film that would become notorious for its racist content - D.W. Griffith's The Birth of A Nation. Despite putting their lives on the line on behalf of America, these soldiers knew what was waiting for them when they returned home.

When I started my life as a film buff back in high school, I sought out as many classics as I could. Most of us start with the ones that get name-dropped the most when it comes to the history of film - Citizen Kane, Casablanca, The Godfather, Seven Samurai, etc. Another name I had heard quite often was The Birth of a Nation, although I avoided it because of both its massive length (nearly 3.5 hours) and its reputation as a horribly racist movie. Did I really want to spend that much time on something so pernicious? Not really. During my second year at NYU, the choice was made for me.

The silent film course was one of my favorites. I discovered all sorts of brilliant films from that era. We even had a professional musician come in and play the piano accompaniment to the experimental Russian classic Man With A Movie Camera. It left me with a love of silent cinema that continues to this day...and it's a strong love indeed if it could survive a screening of The Birth of A Nation. Most of the students in the class were also seeing it for the first time - perhaps they had avoided it for the same reasons. Movie classes at NYU typically ran 4 hours in order to accommodate a movie screening and a lengthy discussion afterwards, but Birth took up almost the entire class just to watch. The experience was far more memorable than if I had simply watched it alone.

When you go into the movie with knowledge of its reputation, you sit there waiting for the bad stuff to start. It doesn't come right away. At first, it's a Civil War re-enactment played straight with most of the racism relegated to subtext. For example, the movie never acknowledges the Southern attack on Fort Sumter that began the war and treats the conflict as this mysterious force that just came out of nowhere and disrupted everyone's lives. There is also one scene I remember where black onlookers cheered for a Southern victory (Hooray! We're still slaves!). Strangely enough, Abraham Lincoln is treated with a lot of reverence and the scene of his assassination is probably the most impressive moment in the film. Unfortunately, it's also the point at which the movie conjures up this bizarre alternate history of the Reconstruction era where blacks took over the legislature and began to punish the defeated South. A lot of problems here, the biggest being that the movie doesn't believe this history is "alternate."

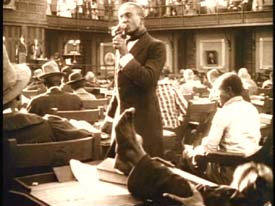

The class had been dead silent through the movie up until this point. I remember when the first gasps came. It was a scene during the election where white people were intimidated into not voting while black officials stuffed the ballot box (A century later, conservatives are still afraid of this). The new black legislators recline in their chairs and put their feet up while guzzling liquor and eating fried chicken. I am not kidding. As viewers, we're meant to be appalled at the lack of respect these men had for a system of government that had endorsed their slavery until just recently. The leader of this radical movement is a half-white/half-black man named Lynch. Not kidding about that either.

On one fateful day, the white hero is depressed about all the black people and sits alone on a tree stump. Suddenly, he sees two children pretending to be ghosts by wearing a white sheet. You can practically see the light bulb appear over his head. Sure enough, the Ku Klux Klan is born and The Birth of a Nation treats them like the goddamn Fellowship of the Ring. They ride across the land in epic scenery shots that were far beyond anything audiences had seen at the time. In the climactic sequence, distressed white people hide inside a shack while hordes of angry black men tear down the walls, a scene that would later become a staple in zombie movies. Contrary to popular belief, D.W. Griffith did not "invent" parallel editing with this sequence, but he did demonstrate how effective it could be in regard to building tension.

Speaking of tension, it hit a fever pitch during my classroom screening during one infamous scene. A young white girl is chased through the woods by a black man and when she gets cornered at the edge of a cliff, jumps to her death rather than risk miscegenation. The obnoxious intertitles tell us not to mourn because she chose death over being defiled. The man is hunted down by the KKK and put on trial. Cut to a horrifying image of a Klan mob restraining him with burning crosses in the background while the screen has a hellish red tint. A brief intertitle pops up. "Guilty." At this point, the class abruptly broke out into laughter. As if there was any doubt how that scene would end. The sheer cognitive dissonance of this sinister image of persecution being presented as an example of righteous justice was too much. The man is killed and the Klan drops his dead body at the front door of the statehouse cause you know, that's just what civilized people do.

Were we assholes for laughing? I don't know. But we had been sitting through this nonsense for two and a half hours and we needed some kind of release. The class continued to laugh at the rest of the film's racist moments because what else can you do at that point? The final scene, of a translucent (and obviously white) Jesus giving an approving smile to everything that has just happened, was the jaw-dropping cherry on top of this shit sundae. We had all expected something pretty bad, but wow. Needless to say, the conversations as we left the classroom were memorable.

The movie was controversial from the start but still a sensation with audiences. President Woodrow Wilson even screened it in the White House. It was used as a recruiting tool for the KKK and is said to have been the inspiration for many spontaneous acts of violence against black citizens. Makes Natural Born Killers look pretty harmless by comparison. D.W. Griffith was bewildered by the accusations of racism (I know, I know) and tried to make amends with another three hour epic, Intolerance, about the struggles of oppressed people through the ages. The Academy Awards wouldn't exist for another 14 years and I'm sure current members are grateful for that, given that an honorary Oscar was given to Al Jolson for his blackface routine in The Jazz Singer during that first round of awards in 1929. Ten years later, the Best Picture Oscar went to Gone With The Wind, a less outwardly offensive film than Birth of a Nation but still infused with that victimized plantation mentality.

Film critics still tie themselves in knots trying to reconcile their feelings about this movie. Never has the difference between a "influential" film and a "good" film been so glaringly apparent. Griffith's innovative techniques and the overall grandiosity of the movie ensured it a permanent place in American film history, a curse on our otherwise impressive contributions to cinema that we brought upon ourselves. As repulsive as it is, I still think anyone seriously interested in film, history and the intersection of the two should watch it. Most of the time, movies about America's sordid racial past depict a conflict between good white people and bad white people in an effort to make us feel better. By showing us the kind of mentality that was mainstream 100 years ago, this movie is actually far more educational.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment